Police and firefighters arrived at the disaster scene within minutes, as did over a hundred sailors from the Navy ship USS Nantucket. “Only an upheaval, a thrashing about in the sticky mass, showed where any life was.” “Here and there struggled a form-whether it was animal or human being was impossible to tell,” a Boston Post reporter wrote. The barman used the makeshift boat to rescue his sister, Teresa, but his mother and younger brother were among those killed in the disaster.Īlmost as quickly as it had crashed, the molasses wave receded, revealing a half-mile swath of crushed buildings, crumpled bodies and waist-deep muck. “When I awoke, it was in several feet of molasses.” Clougherty nearly drowned in the gooey whirlpool before climbing atop his own bed frame, which he discovered floating nearby. “I was in bed on the third floor of my house when I heard a deep rumble,” he remembered. Martin Clougherty, having just woken up, watched his home crumble around him before being thrown into the current. The nearby Clougherty house, meanwhile, was swept away and dashed against the elevated train platform. The Boston Globe would later write that the force of the molasses wave caused buildings to “cringe up as though they were made of pasteboard.” The Engine 31 firehouse was knocked clean off its foundation, causing its second story to collapse into its first. Antonio lived but suffered a severe head injury from being flung into a light post. Maria was suffocated to death by the molasses, and Pasquale was killed after being struck by a railroad car. Antonio di Stasio, Maria di Stasio and Pasquale Iantosca were all instantly swallowed by the torrent. Even the solid steel supports of the elevated train platform were snapped. A fifteen-foot wall of syrup cascaded over Commercial Street at 35 miles per hour, obliterating all the people, horses, buildings and electrical poles in its path. “A rumble, a hiss-some say a boom and a swish-and the wave of molasses swept out,” the Boston Post later wrote. Before residents had time to register what was happening, the recently refilled molasses tank ripped wide open and unleashed 2.3 million gallons of dark-brown sludge. At his family’s home overlooking the tank, barman Martin Clougherty was still dozing in his bed, having put in a late-night shift at his saloon, the Pen and Pencil Club.Īt around 12:40 p.m., the mid-afternoon calm was broken by the sound of a metallic roar. Near the molasses tank, eight-year-old Antonio di Stasio, his sister Maria and another boy named Pasquale Iantosca were gathering firewood for their families. At the Engine 31 firehouse, a group of men were eating their lunch while playing a friendly game of cards.

Temperatures on the afternoon of January 15, 1919, were over 40 degrees-unusually mild for a Boston winter-and Commercial Street hummed with the sound of laborers, clopping horses and a nearby elevated train platform. By 1919, the largely Italian and Irish immigrant families on Commercial Street had grown accustomed to hearing rumbles and metallic creaks emanating from the tank. At least one USIA employee warned his bosses that it was structurally unsound, yet outside of re-caulking it, the company took little action. The container started to groan and peel, and it often leaked molasses onto the street. The company had built the tank in 1915 when World War I had increased demand for industrial alcohol, but the construction process had been rushed and haphazard.

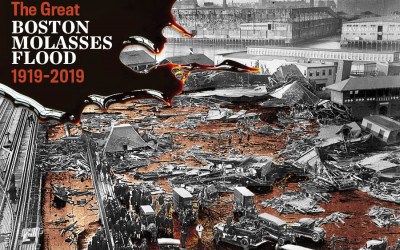

Its sugary-sweet contents were the property of United States Industrial Alcohol, which took regular shipments of molasses from the Caribbean and used them to produce alcohol for liquor and munitions manufacturing. The source of what became known as the “Great Molasses Flood” was a 50-foot-tall steel holding tank located on Commercial Street in Boston’s North End.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)